Photo Notes

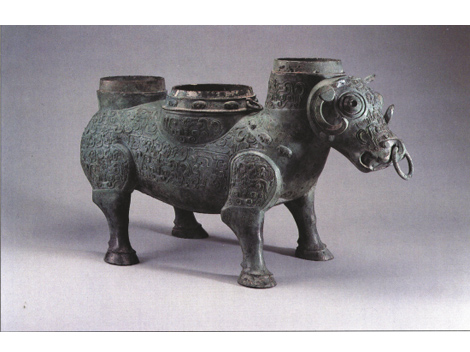

Xi Zun, literally meaning "wine vessel in the shape of a sacrificial ox," was a bronze container used in ritual ceremonies in the late Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC).

It was typically used for storing and pouring wine by the descendants of the old Warring State Qi royal family whose kingdom was in today's Shandong Province.

The Xi Zun displayed in the Shanghai Museum is (Picture 1), however, more than a wine container.

It not only stored the wine but also kept it warm and is the only bronze piece discovered which combines the two functions.

The Xi Zun was found in 1923 in Liyucun Village, Hunyuan Town, in Shanxi Province, with a large number of other bronze vessels.

The discovery excited archeology circles at the time, but unfortunately most of the objects were lost or exported overseas.

Only a few remained and though the Xi Zun survived, the ox unfortunately lost its tail. There are three gaps on the back of the ox and it is presumed that they would have had covers.

A container in the shape of a removable pan was placed in the middle space when the vessel was in daily use.

The body of the ox is hollow inside and this is how wine kept in the pan was warmed. Hot water was poured into the hollow through the other two openings on the back.

Beautiful patterns of animal-like symbols have been stamped into the body of the bronze ox.

Their expressions are light-hearted and relaxed rather than somber and serious as was typical in the earlier Western Zhou Dynasty (c.11th century-770 BC).

Patterns of animal faces around the ox's head and the borders of the openings, however, are more lifelike where the others are symbolic, reflecting the transformation from symbolism to realism over the periods of the changing dynasties.

According to the Shanghai Museum, the technique used in making the patterns was innovative at the time.

Craftsmen made models of the patterns and stamped them one after another inside the body of the vessel mould, a more efficient way to make patterns on bronze.

The ox has a ring in its nose, indicating it was domesticated, and the vessel is therefore not only a valuable antique, but also significant evidence of domestic life dating back more than 2,000 years.

Xi Zun, literally meaning "wine vessel in the shape of a sacrificial ox," was a bronze container used in ritual ceremonies in the late Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC).

It was typically used for storing and pouring wine by the descendants of the old Warring State Qi royal family whose kingdom was in today's Shandong Province.

The Xi Zun displayed in the Shanghai Museum is (Picture 1), however, more than a wine container.

It not only stored the wine but also kept it warm and is the only bronze piece discovered which combines the two functions.

The Xi Zun was found in 1923 in Liyucun Village, Hunyuan Town, in Shanxi Province, with a large number of other bronze vessels.

The discovery excited archeology circles at the time, but unfortunately most of the objects were lost or exported overseas.

Only a few remained and though the Xi Zun survived, the ox unfortunately lost its tail. There are three gaps on the back of the ox and it is presumed that they would have had covers.

A container in the shape of a removable pan was placed in the middle space when the vessel was in daily use.

The body of the ox is hollow inside and this is how wine kept in the pan was warmed. Hot water was poured into the hollow through the other two openings on the back.

Beautiful patterns of animal-like symbols have been stamped into the body of the bronze ox.

Their expressions are light-hearted and relaxed rather than somber and serious as was typical in the earlier Western Zhou Dynasty (c.11th century-770 BC).

Patterns of animal faces around the ox's head and the borders of the openings, however, are more lifelike where the others are symbolic, reflecting the transformation from symbolism to realism over the periods of the changing dynasties.

According to the Shanghai Museum, the technique used in making the patterns was innovative at the time.

Craftsmen made models of the patterns and stamped them one after another inside the body of the vessel mould, a more efficient way to make patterns on bronze.

The ox has a ring in its nose, indicating it was domesticated, and the vessel is therefore not only a valuable antique, but also significant evidence of domestic life dating back more than 2,000 years.

Further Details

• Date added: Dec 20th 11, 09:06

• Photo ID: 276

• Category: жЮњжЊютЎе

• Story: welcome to chinaartweb.com!

• Other Sizes: BlogSize

• Date added: Dec 20th 11, 09:06

• Category: жЮњжЊютЎе

• Story: welcome to chinaartweb.com!

Photo Statistics

• Hits: 421

• Last Visit: 16 hours ago

• Rated 5 by 1 persons

• Hits: 421

• Last Visit: 16 hours ago

• Rated 5 by 1 persons

•

Rate now: